Tapestry of trouble

Donna Haraway, Otobong Nkanga, and Pema Chödrön show that resilience is found in acknowledging our connections and how we move through the trouble—not in trying to escape it.

“We—all of us on Terra—live in disturbing times, mixed-up times, troubling and turbid times''

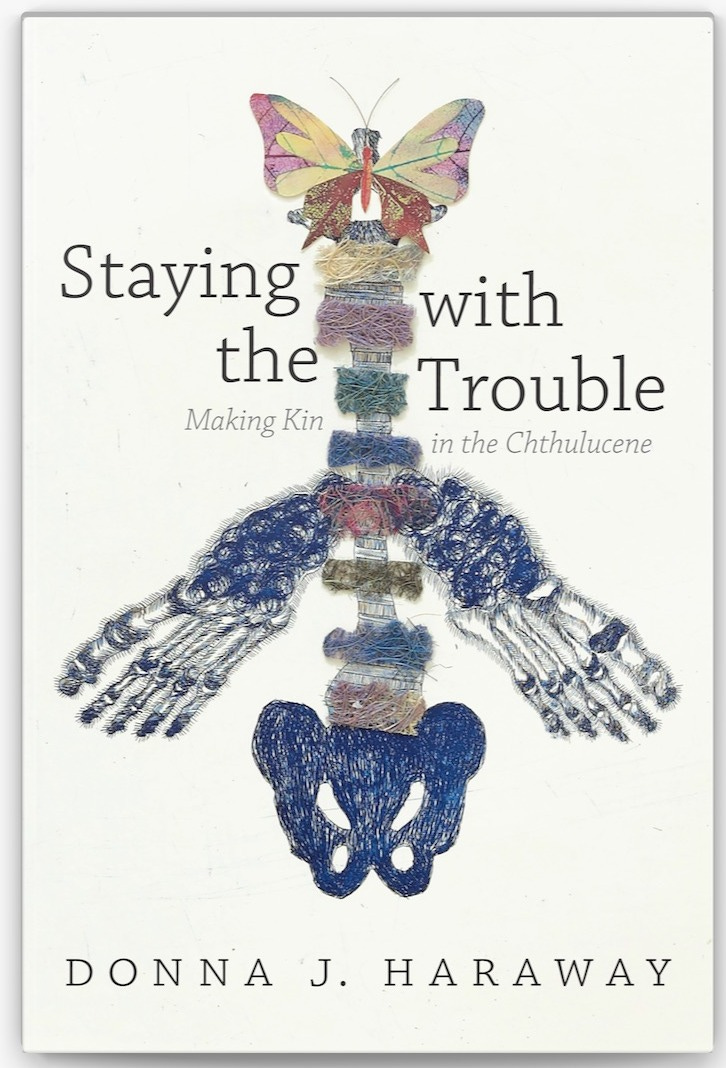

Says Donna Haraway, a scholar of spirituality, feminism, and science who has pioneered new ways of thinking about art, biology, climate change, and physics. She uses turbid times to describe the current state of our life on earth in her 2016 book “Staying with the Trouble.” Below is an image of her book’s cover, one of my favorites, visualizing interconnectivity across species.

In her book, Haraway suggests three paths forward. We could see the world as already lost, too late for us to intervene (Depressing). We could continue to invent elaborate “technofixes” to escape the mess we’ve made, like using geoengineering to fight climate change without addressing its root causes (Escapism). Or we could do something harder: “stay with the trouble,” following threads that craft new stories for our ongoing life on earth (Complicated, but maybe rewarding).

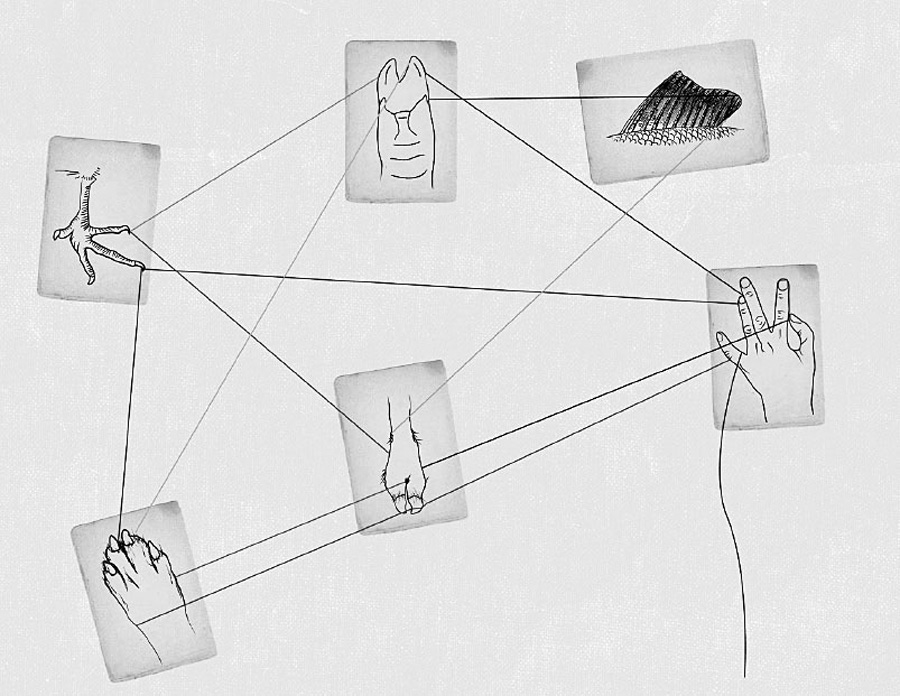

This third option centers on the power of staying present, cultivating what Haraway calls “multispecies justice”—justice not just for humans but for animals, plants, rivers, and ecosystems. By staying present, we can begin to notice the threads that connect us to the world around us and weave new stories, or “sfs” (Haraway’s term for string figures, science fictions, speculative futures…read more here). These SFs could allow humans and nonhumans to shape a livable world together. She writes in “Staying with the Trouble”:

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts thinking thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.”

These SFs seem abstract, but they play out in everyday moments. Imagine stirring local honey into your morning tea. Honey comes from bees… from the flowers they pollinate… from the gardener who grew the plants…from the soil that made it all possible.

When we start to imagine these SFs, we gain awareness and can begin to ask questions. Where was the honey produced? Was it really local? What pesticides were used? How did that impact the larger, local ecosystem? Each thought is a thread that connects us to the larger web of life. While this tiny realization most certainly won’t solve climate change, visualizing these small sfs reminds us of our deep entanglement with the world—plants, animals, humans, etc. Visualizing a web like the below could impact our actions moving forward.

Harraway doesn’t want us to drown ourselves in the negativity of the trouble. She wants us to stay with it. To look at it.

Harraway’s request reminds me of Pema Chödrön, an American-born Tibetan Buddhist, whose teachings also emphasize facing uncertainty and discomfort. In her book, “When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times,” she aptly describes this looking:

“Rather than letting our negativity get the better of us, we could acknowledge that right now we feel like a piece of shit and not be squeamish about taking a good look.”

Face our fear, uncertainty, and nuance (think ecotones). Sounds painful. Chödrön argues this is the path toward a mindset that can handle paradox and ambiguity, much like Haraway’s call to face the trouble. Chödrön writes:

“As human beings, not only do we seek resolution, but we also feel that we deserve resolution. However, not only do we not deserve resolution, we suffer from resolution. We don't deserve resolution; we deserve something better than that. We deserve our birthright, which is the middle way, an open state of mind that can relax with paradox and ambiguity.”

I think artists are best at visualizing SFs that help us see the world differently and perhaps act differently too. Otobong Nkanga, a Nigerian-born visual and performance artist, whose work embodies the middle way that Pema Chodrin offers. She creates her own SFs that blend multiple perspectives, mediums, and histories into her fiber pieces.

A few weeks ago, I had the joy of seeing Otobong Nkanga’s in-process installation at the MoMA. Her show, “Cadence” officially opened on October 10th and will remain open until Summer 2025. She is absolutely brilliant.

Otobong Nkanga explores themes of interconnection, focusing on the relationships between nature, humans, and systems of commodification—much like Haraway’s call to stay with the trouble and recognize our entanglement with the nonhuman world. Otobong allows many opposing realities to be true in one tapestry of trouble. Both Nkanga and Haraway highlight the importance of acknowledging these interdependencies rather than escaping them, with Nkanga weaving these ideas quite literally into her fiber work.

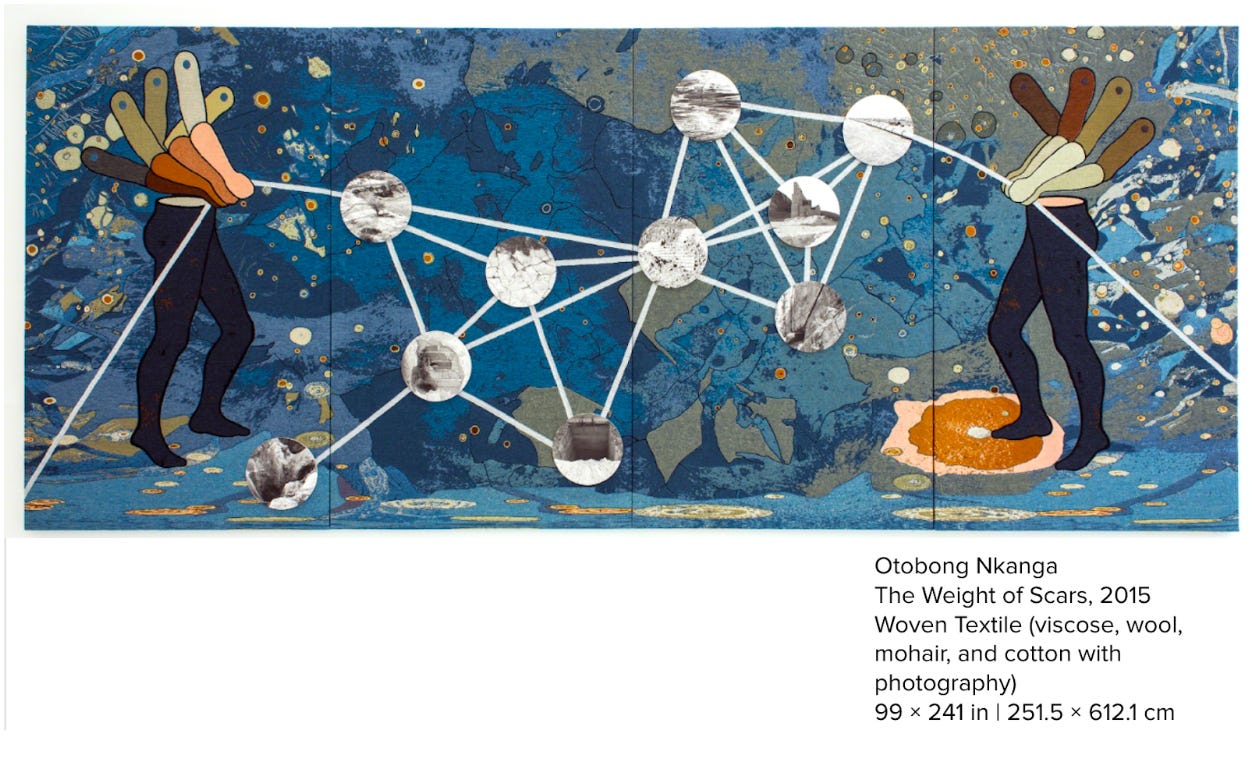

Nkanga’s practice spans various media, including tapestry, installation, and performance, blending art with social, ecological, and political issues. Nkanga’s artistic process is recursive. Like a set of Russian dolls, each layer of her work embeds and mirrors the concepts she explores. Nkanga uses fibers, weaving them into constellations and diagrams that chart the interconnections between species, societal issues, material production, and climate change. Her use of weaving serves as a poetic metaphor for integrating materials and ideas. Haraway describes the act of pulling fibers from tangled events and following the threads to see where they lead, crucial for "staying with the trouble."

Her relationship with fibers is deeply personal, rooted in her childhood when she and her mother sold hand-dyed Batik fabrics to designers. She notes how fibers carry social and economic messages, preserving power and communicating status. Weaving, an ancient art form, pulls together distinct threads to create something cohesive. Nkanga sees these fabrics as markers of wealth, functional objects, and even a way to craft new worlds beyond the reality of a living space (sfs). When you look at them, they feel otherworldly—somewhere between under water and in outer space. Through her work, Nkanga weaves educational narratives about the entanglement of humans and the earth, leaving room for the viewer to interpret and act.

She often omits heads on the figures in her work, believing it draws too much attention to the individual, distracting from the collective and the deeper interconnections at play. The Weight of Scars (2015) is a vibrant orange and blue tapestry, similar to her MoMA installation. It depicts two headless figures suspending images of Namibian mines across rope-like constellations, linking the personal and environmental scars of colonialism to a broader narrative of exploitation. The layering of abstract shapes and blue-green tones allows viewers to envision the piece in space, underwater, or on earth, reinforcing humanity’s intertwined relationship with the planet. To me, this piece stays with the trouble of the beauty and the destruction of the relationship. I don’t know that it offers a solution, but it lets us think about the role we play.

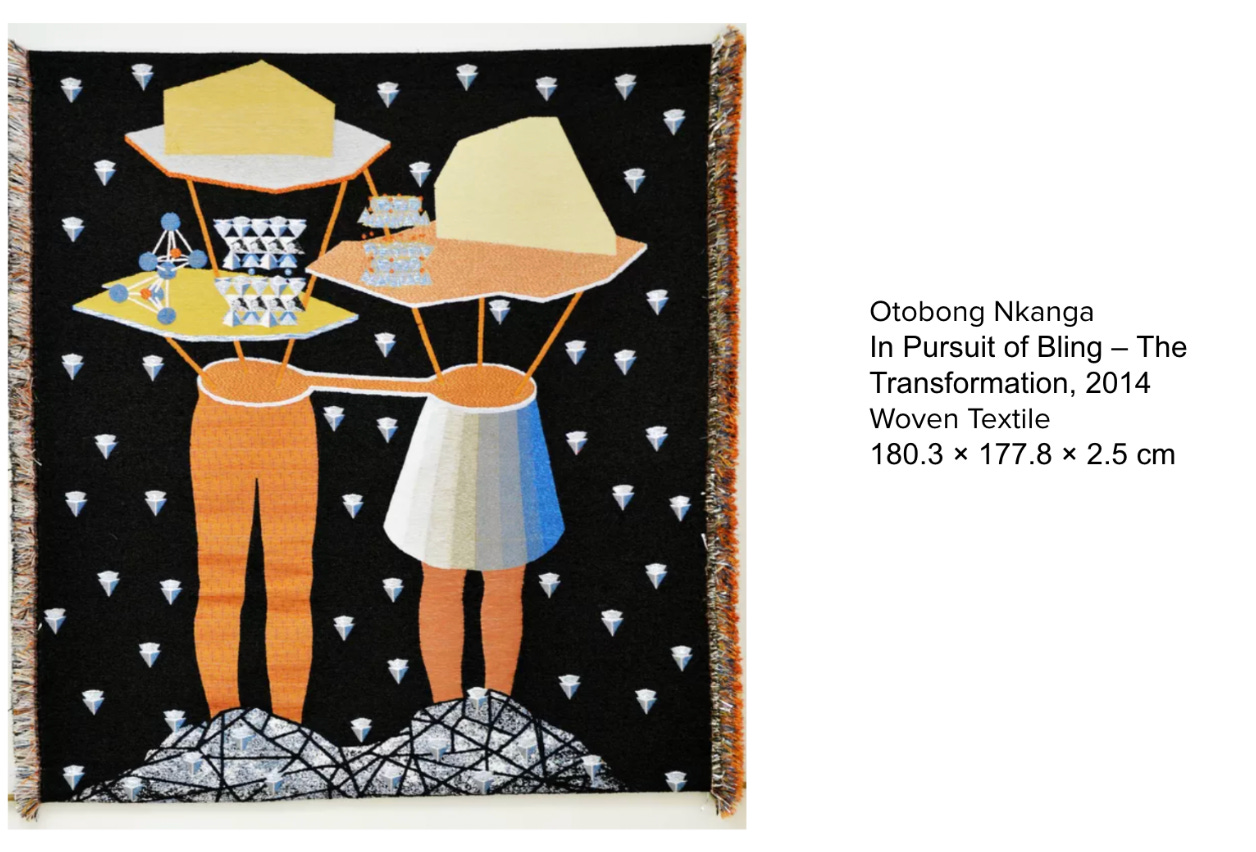

Minerals play a central role in Nkanga’s exploration of commodities. She often uses or depicts minerals like mica, which sparkles in makeup products but has a dark origin rooted in human and environmental exploitation. In Pursuit of Bling: The Transformation (2014), Nkanga examines how the glittering appeal of mica contrasts with the ecological damage and human labor it requires. The piece features male and female figures tied together at the waist, connected to rock formations and floating jewels, visually linking the earth’s resources to human consumption.

Nkanga explains that her interest in minerals stems from their cyclical nature—we ingest minerals to sustain our bodies, and when we die, our bodies return to the earth, becoming minerals once more. This circular relationship is woven into her work, where the beauty of her tapestries contrasts with the darker realities of commodification and displacement.

Donna Haraway, Otobong Nkanga, and Pema Chödrön each offer ways of engaging with the uncertainties and complexities of our world. Nkanga’s tapestries, much like Chödrön’s call to stay present with discomfort, reflect the strength that comes from navigating rather than avoiding complexity. At least we don’t have the pain that comes from avoidance…we have the certainty of uncertainty.

All three women challenge us to face the interdependencies that shape our lives and the world around us, showing that resilience is found in acknowledging our connections and how we move through the trouble—not in trying to escape it.